“I’m rotten to the heart,” Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) confesses with breathless bitterness in Billy Wilder’s classic 1944 noir, “Double Indemnity.” Eighty years ago this month, Wilder and Stanwyck established Phyllis as the archetype of the femme fatale — a misogynist fever dream of seductive, heartless femininity.

This week, Richard Linklater’s “Hit Man” picks up the femme fatale and takes her for another run at her usual narrative — seducing a good man with doe eyes and promises of sex and money. Things have changed a good bit in the ensuing decades, though. Women’s desires aren’t quite as threatening to the patriarchal order in today’s Hollywood. “Hit Man” suggests that when backing away from misogyny, men, too, have more options, more happiness and more love.

The femme fatale is generally defined as a seductive, scheming, evil woman who leads men to ruin and death. The trope dates back at least to Greek myths about figures such as the enchantress Circe, who turned men into pigs, and the Sirens, who lured men to a watery grave.

“Double Indemnity” turned the trope into an indelible archetype for the morally ambiguous world of film noir. Walter (Fred MacMurray) is an upright insurance agent, who falls hard for bored housewife Phyllis, with her carefully jiggling anklet and her plan to off her husband for the insurance money. She leads Walter inevitably to ruin — but not before he realizes the depths of her depravity. They shoot each other, but only he survives (barely).

Wounded, Walter staggers back to his office to confess to his irascible but good-hearted boss, Keyes (Edward G. Robinson). Just before the film ends, Walter tells Keyes, “I love you”— a not-really-ironic declaration of chaste homosocial patriarchal bonding which is presented as the only alternative to intercourse with nefarious femininity.

Femme fatales began to be reworked in the neo-noirs of the 1980s and 1990s. Wilder, and filmmakers like him, made classic noirs in which the patriarchal order won out; evil, lustful, greedy women like Phyllis would be justly punished. As feminism made inroads, though, filmmakers were less certain that patriarchy would win, and even occasionally less certain that it should.

In neo-noirs including “Body Heat” (1981), “Basic Instinct” (1992), “The Last Seduction” (1994) and “Gone Girl” (2014), the femme fatales are more resourceful, more dangerous and more attractive because their machinations are more successful. John McNaughton’s “Wild Things” (1998), in particular, openly roots for its wicked bisexual female protagonist to outwit every sleazy man (and woman) to get away with the cash.

Recently, there’s been a spate of films — often with female creators — that contort the femme fatale in ever more seductively ambiguous poses. Just looking at films from last year, Justine Triet’s “Anatomy of a Fall” won’t tell us if its protagonist is a murderer or an innocent bystander — instead suggesting that our familiarity with the femme fatale trope warps our perspective on independent, successful, sexually active women.

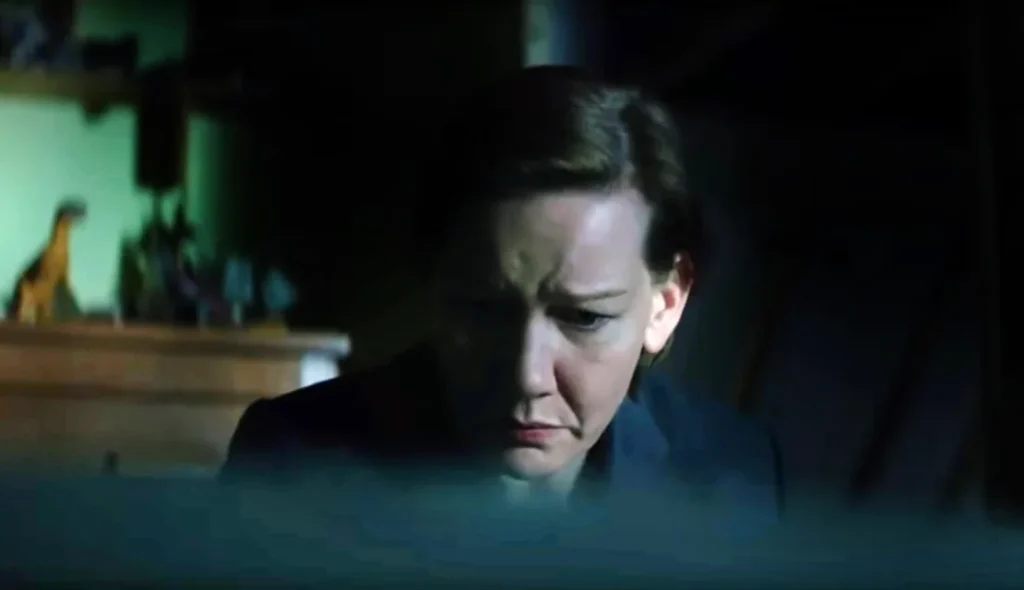

Emerald Fennell’s “Saltburn” scrambles the noir’s gender dynamics and makes its femme fatale a bisexual, social-climbing deceitful young man. William Oldroyd’s “Eileen,” based on Ottessa Moshfegh’s novel, is about a homoerotic relationship between two women who exchange positions as corrupting femme fatale and innocent corrupted, until the real evil turns out not to be the bad women at all, but the good woman who colludes with patriarchal violence.

Linklater’s “Hit Man” isn’t as daring as “Anatomy of a Fall” or “Eileen.” But its laid-back blurring of the line between rom-com and noir builds, like them, on those eight decades of imagining and reimagining the femme fatale.

In this case, the femme fatale, Maddy Masters (Adria Arjona) is largely stripped of her power. Like Phyllis, she wants out of a miserable marriage, and thinks killing her husband is her only option. Unlike Phyllis, though, she’s hesitant. She’s not a quintessence of misogynist evil and not an all-knowing, ice-cold manipulator: She’s just a person with bad options contemplating bad decisions.

The guy Maddy pulls into her not-really-a-web is Gary Johnson (Glen Powell), a nerdy philosophy teacher moonlighting as an undercover hitman named Ron for the police. Gary gets would-be clients for murder on tape so they can be prosecuted and jailed. But when Maddy asks him to murder her husband, Gary falls for her story and her considerable charm. He dissuades her from following through. Or does he?

Whatever the answer, the two quickly embark on a passionate and kinky love affair. Phyllis turns Walter into a different person in “Double Indemnity,” and Maddy does the same to Gary/Ron in “Hit Man.”

The difference between the films is that since Maddy isn’t some nightmarish force out of the patriarchal unconscious, her influence on Gary doesn’t really look like corruption. Instead, it looks more like two people who change each other because they care about each other, and caring about someone changes you. They lie to each other a lot at first, but as the plot closes in around them, they switch to honesty with remarkably little fuss. Powell’s and Arjona’s chemistry is off the charts in part because they are both extremely attractive Hollywood stars, but mostly because they and Linklater sell the conceit that these two people genuinely like being together.

Most reworkings of the femme fatale have, understandably, been efforts to negotiate, or think about, the trope’s misogyny. “Hit Man” also addresses how noir traditionally robs men of agency and of the possibility of love. If competent, adult, complicated, sexual women are evil, emotionless manipulators like Phyllis, heterosexual men can either be bone-headed dupes or forswear intimacy altogether. The patriarchal world of “Double Indemnity” is as bleakly loveless for men as it is for women.

Some today still idolize the rigid, black-and-white world and gender roles of 80 years ago, and are trying to turn back the clock. “Hit Man,” and other contemporary noir films, in contrast, are trying to imagine a way out of the “Double Indemnity” double bind. We’re supposed to believe that it’s dangerous to love the femme fatale. But in this, as in most things, the real danger is misogyny and hate.